How the Rosary Evolved

The basic form of the Rosary has been in place since the 16th century. It has its roots in the liturgical prayer of the church and the ordering of the day in the monastic tradition. It was known as ‘the poor man’s Breviary,’ The Breviary being the book containing the liturgical texts followed by the ecclesia. The rhythm of the monastic day was structured around 150 Psalms and the laity wished to follow this pattern of devotion. As most people could not read, or afford a book, they were given beads to count while saying the Our Father 150 times a day. If they did not have beads, they counted their prayers on ribbon or string or rope tied with 150 knots.

Mary had always been an important part of the Christian story, being given the title Theotokos – “the one who gives birth to God”– in the 4th century. But after the patristic period ended with the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, Mary’s place in the Eucharistic liturgy further emerged. She was seen as both a key figure in the life of Jesus and as a transcendent personage of holiness on her own. The words of Luke 1:28 “Hail Mary full of grace, the Lord is with thee” found its way into common usage. This phrase was then linked to Elizabeth’s greeting to Mary in Luke 1:42, “Blessed art though among women and blessed is the fruit of thy womb Jesus.” The first half of the Hail, Mary was formed. It was prayed along with the Lord's Prayer and the Psalms.

Over time, the 150 Psalms were divided into sets of ten, with an Our Father said at the beginning of each set. When some of the monasteries began to meditate on aspects of Jesus' life along with the Psalms, they reduced the number of ‘meditations’ to fifty, and then again, to fifteen: five joyful mysteries; five sorrowful mysteries, and five glorious mysteries. A final line was added to the Hail Mary and this prayer was repeated in sets of ten. By the end of the fifteenth century, the basic form that is used in the Rosary today was in place. In 1569 Pope Pius V put his formal stamp of approval on the praying of the Rosary.

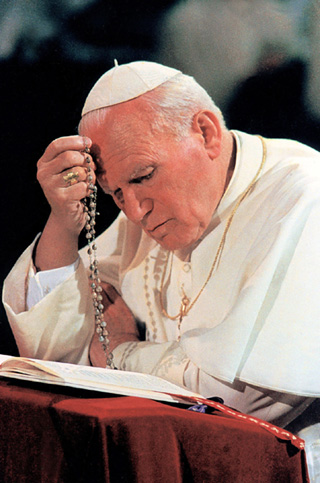

Pope John Paul II introduced the last set of mysteries, the luminous mysteries, in the 1980’s. John Paul II, a great proponent of the Rosary, wished to breathe new life into the practice while also emphasizing the ministry of Jesus and his teaching. In his Apostolic Letter, Rosarium Virginis Mariae, in 2002, he called the Catholic church back to the spiritual practice of praying the Rosary on a daily basis. At the conclusion of his passionate plea, he writes:

“The Rosary is a prayer for peace because of the fruits of charity, which it produces. When prayed well in a truly meditative way, the Rosary leads to an encounter with Christ in his mysteries and so cannot fail to draw attention to the face of Christ in others, especially in the most afflicted. How could one possibly contemplate the mystery of the Child of Bethlehem, in the joyful mysteries, without experiencing the desire to welcome, defend and promote life, and to shoulder the burdens of suffering children all over the world? How could one possibly follow in the footsteps of Christ the Revealer, in the mysteries of light, without resolving to bear witness to his “Beatitudes” in daily life? And how could one contemplate Christ carrying the Cross and Christ Crucified, without feeling the need to act as a “Simon of Cyrene” for our brothers and sisters weighed down by grief or crushed by despair? Finally, how could one possibly gaze upon the glory of the Risen Christ or of Mary Queen of Heaven, without yearning to make this world more beautiful, more just, more closely conformed to God’s plan?”

The Conestabile Madonna pointed by Raphael 1502 – 1504 in Umbria, Italy. Just a little throw away toss off to pay the rent for Raphael, and all these years later, we still marvel.